31 minutes

Assessing your site for Search Engine Optimization (SEO)

I mentioned in another post that I’m open to doing site assessments for a few non-profits, mostly focused on performance, but intended to touch upon SEO and Accessibility along the way. If you work on a website and want to do your own self-assessment, I thought I would run through a brief discussion of what I would look at and what I recommend. Today’s post focuses on SEO, discussions around the other topics will follow!

What is SEO? #

Search engines are a key method for users to find anything on the web, including your happy little site, and Search Engine Optimization (SEO) is the practice of making sure your content shows up in those search results. You’d be surprised how many guides move on to “tips and tricks” without going over the basic, fundamental improvements in the structure of a site. Skipping these fundamentals is detrimental when it comes to search engines picking up your content accurately. It’s that underlying foundation that I want to cover here. Once you’ve ensured your foundation is solid, there may absolutely be a place for tips and tricks to improve your ranking. There are multiple search engines out there, but I’m going to focus on Google for two reasons. First, if it works for them, it should work for Bing and other search engines as these are standard methods. Second, Google is going to be the primary search engine your users are searching in. Depending on where you are in the world, that might not be true, in which case see my first point, but also you can dig into to how you appear in whatever search engine is most popular for your audience.

Why is it important? #

Your target audience may have a few ways to find your site, but one of the most common avenues is going to be through Google or another search engine. If your content isn’t showing up accurately (or at all) in these search results, then you will be missing potential visitors.

What is our goal? #

Search engines build up their index of pages (the collection of stored data that they run searches against) by crawling sites. They programmatically request a page on your site, read the text, extract all the meaningful bits of info they can find, and follow any links to try to find any other pages to index. For every piece of content on our site that we want people to discover, we need the search engine to be able to find it, pull the right information out of it, and to display it accurately in search results. This system of crawling pages is very advanced and can handle a wide variety of content, but we can make it easier or harder for it to understand our pages.

Tools to assess the state of your SEO #

You can’t call Google up and ask them if your site is written correctly, but you can do the next best thing through a few special types of searches and the Google Search Console.

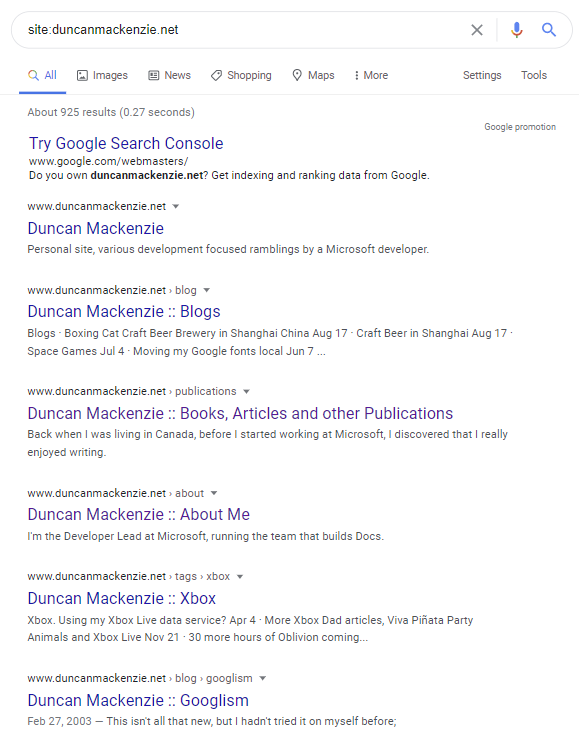

What’s showing up in Google? #

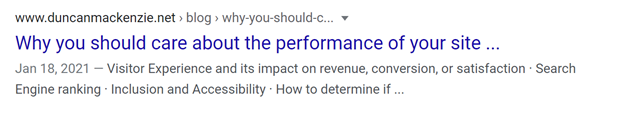

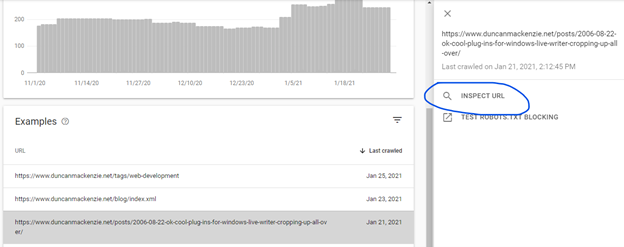

The first “trick” is to go to Google and do a search that scoped to just your site. For example, searching on `site:duncanmackenzie.net` will return all of the entries Google has for my domain. If you add a search term to that, like `site:duncanmackenzie.net performance`, you can see what pages on your site come back for that term. Without the term, you’ll be seeing a list sorted in terms of what Google thinks are the most relevant pages on the site and it may seem a bit random. This set of results can be informative, as it shows how your content is going to look in a regular search result. This includes what is going to show up as a title and description.

Is it showing the title you want for each of your pages? Does the description make sense? If it is showing a date, is it showing the right one? If you are happy with what you are seeing, then that’s a great first test. In general, that means Google is indexing your pages accurately. If the results aren’t what you’d like to see, we will be discussing titles and descriptions a bit later. In my case, looking at the list has given me a list of ’to dos’ to clean up my results. My ’tag’ pages and my blog homepage are both listed, and I don’t think I want them in there (they are useful to find content, but they aren’t content themselves). We’ll cover how you can control this later as well.

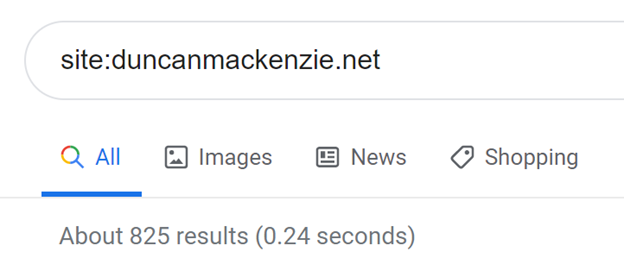

The second aspect of testing via doing a search, is to see how many of your pages are returned. We’ll get to a *better* way to determine that in a moment, but for now check out this # when you do a search:

This number can vary over time, but for my site it says it has around eight hundred results. That’s a reasonable number, since I have about one thousand pages in total. I wouldn’t expect it to be exact, but if it is a much smaller or much larger number than the pages you have, that could indicate an issue.

Introducing the Google Search Console #

A better way to dig into your search engine status, at least with Google, is to use the Google Search Console. You are only able to use this tool to see information about your own site, so in addition to signing in with a Google account, you’ll need to go through a verification process to prove you own a given domain before you can view it. You can upload a html file, add a meta tag to your page, or add a record at the DNS level to prove that you have ownership. If you happen to already be using Google analytics on this site, with the same Google account, then you can verify the site that way as well.

This set of tools and dashboards will show you information direct from Google including:

- How many clicks your content (URLs on your site) have received from Google Search

- How many pages on your site are included in the search index, and more importantly, what errors or issues are preventing some pages from being included

- If you have a sitemap registered for your site (more on that later) and the results of Google indexing that file

- And more!

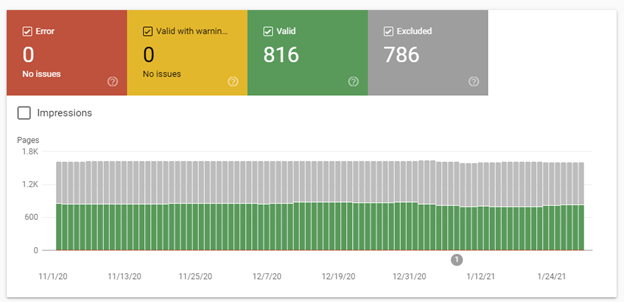

My personal favorite feature in this site is the coverage report. I mentioned before that Google indexes your site by crawling through your pages, and the coverage report tells me how many pages it was able to index successfully (yay!) and any issues it has run into (boo!). For my site, this is the report now:

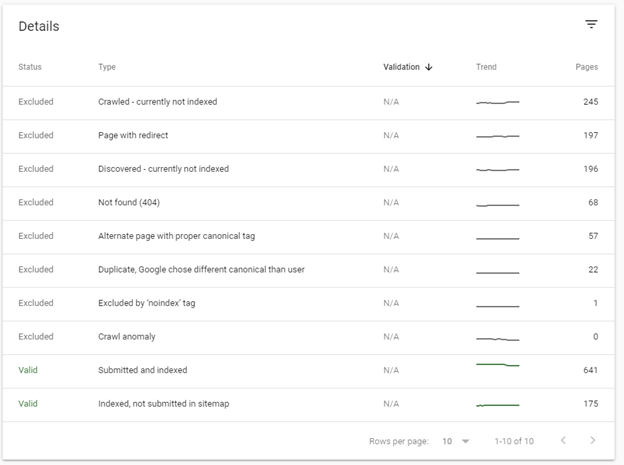

This data shows that it has been able to crawl 816 pages without issue but has found and excluded 786. By drilling in, I can try to figure out why it has excluded some of my pages, and then decide if I care. It is possible that all these excluded pages are ‘by design’, in which case I can ignore them, but it’s worth clicking through.

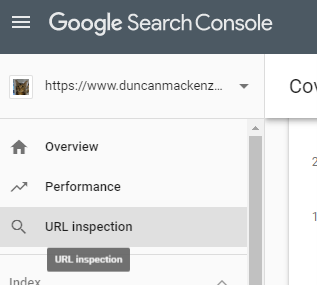

In the list above, I can see that 245 pages were crawled but *not* indexed. If I had intentionally marked them as ’no index’ (more on that later), that would be expected, and if Google hit an error (like getting back a 500 error from the site) that would show up in a different category. If you click on one of these lines, you can see a list of sample URLs. From there, you can click on one, then ‘inspect URL’ to find out more.

At this point, Google gives you detailed information for a given URL. In this page’s case, it shows me that it discovered it by following a link on https://www.duncanmackenzie.net/posts/. Which is interesting, because I don’t know why that page exists or how it is being created. Another ’to do’ for me, figure that out and get rid of it. You don’t want old garbage pages floating around that aren’t part of your site navigation or content. Google is excluding this page, so this isn’t an urgent issue, but I like to tidy things up when I discover anything unintentional.

If you are ever curious why a certain page is showing up, or not showing up, you can also just go directly to looking at individual URLs through the “URL inspection” option in the upper left corner.

It is important to note that, if you are working on a very new site, it is possible that little to no data will be available in the Google Search Console. If that’s the case, one effective way to kickstart getting your site indexed will be to inspect the homepage, and then request indexing (which will cause Google to crawl that page, and hopefully discover all your other content by following links from there), or to submit a Sitemap. We’re going to discuss sitemaps later, but if you have one then the “Sitemaps” menu option along the left side is the way to submit it.

First, do the fundamentals. #

This post is about ‘assessing’ your SEO status, checking if you are showing up in search the way you want to be, but I am going to delve a bit into how to control and improve your status as well. Adding meta tags to your page, creating a sitemap, and using fancy features like structured data are all useful, but if you can focus on the fundamentals, you may find that gets you far enough. What do I mean by fundamentals?

- Build your pages with the correct valid HTML.

- Make your page titles and headings make sense.

- Make sure you can get to all your content by following links from your navigation (even if it takes a couple of steps).

Most of what we do when trying to fix the SEO for a website is to make up for issues with these fundamentals. We create a sitemap (which is a listing of all our pages, designed for search engines to use) to ensure Google and others can find all our content just in case they can’t find it by crawling our pages and just following links. A clear navigation system on the site, with layers of deeper links, accomplishes the same thing and will generally work fine. Having valid HTML on our site, using heading tags like H1 and H2 for our headings, <a> for our links, etc. will also make it easier for search crawlers. If you have a good H1 and an informative intro paragraph, Google will pick that up even if you don’t have a description in your metadata. None of this suggests it is a bad idea to do all the things in the checklist below, but I want to make clear that you will get far with your site’s SEO by just focusing on the fundamentals.

The last fundamental point I would make, is to create useful content. This is subjective of course, but all the technical work in the world isn’t going to get search engine traffic to your site if no one is looking for your content. Luckily, there are so many people on the Internet that it is likely that some of them are going to find your content to be exactly what they are looking for.

Checklist #

This list is a basic set of things you should be looking at on your site, but how you can fix/update them is going to depend on what software you are using. I’m listing them in the order I think you should approach them in, but if you have setup the Google Search Console discussed above, you should make resolving any errors in the coverage report the priority.

Page Titles and Descriptions #

The title of your page is generally what shows up as the main text in search results, making it particularly important for anyone doing a search. Go back to look at the scoped search results for your domain. If you see titles like “Home” for your homepage, that’s not going to be useful when it is somewhere on a page of links to different sites. Ideally, this is a short descriptive version of your primary heading on the page. They both serve a similar purpose, but the title is often shorter as Google is going to cut off anything beyond about 60 characters. I recommend constructing your page titles as a combination of your site information, any sort of category or section name, and the individual page title. Keeping in mind that the most specific information (about the specific page) is the most important, you order these bits of info in reverse (most specific to most general). For a page on my site, for example, I name them like this:

Assessing your site's SEO :: Duncan Mackenzie

In a larger site, where you could have lots of content types, this could become

Assessing your site's SEO :: Guidance :: Duncan Mackenzie

Some sites put a | or a dash between parts of the title, I’m not aware

of any compelling argument for a specific type of delimiter. There is no

harm to a longer title but remember that only a small amount will show

up in the browser tab, and only the first 60 or so characters are going

to show up on Google. Putting the most valuable information first is

key. If you named your pages in the other order, like Duncan Mackenzie

:: <post title>, then a listing of results from your site would be

difficult to parse.

In addition to controlling the title shown in search results, the page title itself is a good signal to Google about the content of your page. Terms used in the title are generally a good indicator about the topic of the page. Google provides more detailed guidance on page titles on their Search Central site.

If you don’t like the title of a page, or the pattern of titles across your site, this is a great first item to fix. After Google has crawled your site again and updated its index (which can take a few days, but you can request a reindex in the search console), this will improve your search result listing.

The second element of the listing that you can control (or at least influence), is the description. If you supply a description in the meta tags of your page, like this:

<meta name="description"

content="Back when I was living in Canada, before I started working at

Microsoft, I discovered that I really enjoyed writing.\" />

Google is likely going to use that as the description shown in search results. It is essentially a suggestion though, you are providing a description that you think is good, and Google will often use it. Sometimes, content from some other part of the page will be shown because it contains the word being searched on, or because Google’s algorithms have decided it’s a ‘better’ description than the one you supplied. If you don’t supply this tag, then Google must try to figure out a description on its own, often pulling a snippet out of the first paragraph of your content. This could be good, but if you want more control then you should write the description explicitly.

If you are writing HTML by hand, then the page title is the <title> tag in the <head>, and the markup for the description meta tag is shown above, but if you are using a CMS then you will need to set this information in the attributes of the page. For a deeper example of how page titles can impact a variety of experiences, I wrote an article about the titles on Channel 9 and suggestions on how to structure them.

URL structure #

I am a huge fan of readable and hackable URLs.

Readable means that they make sense if you read them like a form of navigation and structure. Consider these two URLs:

https://www.duncanmackenzie.net/blog/assessing-your-seo

vs

https://www.duncanmackenzie.net/p/342

Both could work perfectly, but the second is only meaningful to the computer, while the first one tells me this is a blog post and that it is about “assessing your seo”. Like a page title, the URL is another bit of information to provide to the user and to search engines. Google will look at the terms in your URL and consider it as another data point.

Hackable, which is less widely agreed on as valuable, means that I can take a URL, remove a section of it and it should still work and return a logical result. If I have a URL like https://www.duncanmackenzie.net/tags/xbox, I should be able to remove the last part (xbox) and be taken to a list of all tags.

Jakob Neilsen has a great article on this (yes, it is from 1999, but some things are constants on the web). You can also browse around a site I’ve worked on, like Microsoft Docs or Channel 9 and you will hopefully see both rules consistently apply. While we are on the topic of URLs, I’m also a firm believer that you shouldn’t have the technology your site is written in reflected in the URL. No .php or .aspx at the end of your URLs for example. URLs are an address to a piece of content, so the technology you happen to be using is irrelevant to the user. You may also change technology at some point, and while you can setup redirections or other techniques to keep the old URLs working, it is cleaner if you just avoid it in the first place.

Links to all your content #

If someone comes to your site, directly to the homepage or some individual post, it should be possible for them to explore and find all your content. Generally, this means a navigation menu of some kind, index pages (a list of all your blog posts for example), and maybe some handy categorization like tag pages. Of course, there are always search engines, but that shouldn’t be the only way to find content on your site. This type of internal linking, exposing all your content to an interested visitor, is critical for Google as well, as their crawler is going to try to dig through all your pages by following links. Go to your site’s homepage and try it yourself. Can you get to everything on your site just by clicking through links? If you start at an individual page, can you still get to everything, even if that just means clicking on a ‘home’ link and then going from there?

Valid HTML #

Web pages are made up of HTML, or markup, and while browsers are amazingly capable of displaying pages with lots of errors and broken tags, it is easier for Google and the browser if you have well structured and valid markup. This means using both the overall structure of your document (no mismatched tags like a <p> without a matching </p>, <title> is nested inside <head>, etc.) but also using the appropriate markup. You should have a <h1> for your main heading and <h2> for the next level down, anchor (<a>) tags with a href attribute for links, and paragraphs should be text inside <p> and </p>. One quick way to check if your pages are constructed of valid HTML is to go to the W3C Markup Validation Service and enter in a few of your URLs. You will likely get at least a few warnings, my site does (more “to-dos” for my list), but you should focus on “errors” first. In the end, if the site is rendering correctly you may not need to fix that many issues, but this step can catch some problems that the browser is managing to work around. Valid HTML can impact other aspects of your site like performance and accessibility, making it a fundamental worth putting effort into, but depending on your platform/theme it can be difficult to fix every issue. Running my own site through, I had four errors and three warnings, and I have a quite simple site. I can see how to fix the warnings and two of the errors very easily, but the remaining issues would take some reworking of both HTML and CSS. Nothing in this list seems serious though (let me know if you disagree), so I’m not going to spend much time on it.

Sitemaps and robots.txt #

Earlier I mentioned how important it was for you to have navigation and other internal links so that people can find all your content. This is critical for both users and for search engines, but for search engines we have another option, Sitemaps. We can provide a list, or set of lists, of all the individual URLs on our site, in a nice machine-readable format (XML). Google and other crawlers discover these files, if we have them, by requesting a file called robots.txt from your domain. My file is available at https://www.duncanmackenzie.net/robots.txt and listed here:

User-agent: \*

Sitemap: https://www.duncanmackenzie.net/sitemap.xml

Boring and simple, this file just says for every possible crawler (program that indexes sites for a search engine), here is my sitemap. I could add lines to suggest that certain URLs or patterns of URLs be skipped, but in my case, everything is open. The link to my sitemap (which has to be on the same domain, I can’t link off to a file stored somewhere else) is the only usual element in my file, but the full syntax for robots.txt is available if you want to do something more complex.

The sitemap itself is a long list of URLs for my site, but it can also be a ‘sitemap index’ that points off to other files full of links. An index is used if you have a large site, as each file can only contain 50,000 entries. It’s possible to do all sorts of things in this file, such as adding alternate links for localized content and priority values to indicate how important a given URL is relative to the rest, but the simplest form is just a list of URLs.

What you want to check here, as a site owner, is:

- Do I have a robots.txt file? (just add /robots.txt to your domain in a browser and see)

- Does it contain a link to a sitemap?

- Does that sitemap (just paste that link into the browser) exist, and does it seem to contain all my URLs? (if you have 1000s of URLs, I don’t expect you to do an exhaustive audit, but read through and see if it seems to include everything, or search for pages you are especially curious about)

Sitemaps aren’t created manually though, so if your platform isn’t currently creating one, you’ll need to dig into the settings to turn this on. Most CMS platforms will do this automatically, but a custom developed site may have forgotten to support it.

Advanced Topics #

I intended this article to be a ‘quick’ guide to assessing your site for SEO, which makes it seem odd to include an ‘Advanced’ section. These are situations and topics you will run into though, so I wanted to touch on them to at least give you a brief understanding of the concept.

Redirection #

Once you publish something online at a given address (URL), that URL could live forever. You have no realistic way to know if someone has saved it in an internal document, bookmark, email or has included it on one of their web pages. If, at some point in the future, you want to change that URL, then you need to consider what will happen if someone visits the old one. Ideally, you’d want to send the user to the new location. That is a ‘redirect’ and in addition to being important for users (to get them to their desired content), it is also extremely important to search engines. If Google is crawling some other site and hits a link to this old URL, it will follow that link to your site. If you redirect it to a new location, Google will update its index information for that page with the new address. All the pre-existing information Google has on that old URL will transfer to the new URL (in their system), so that you don’t lose any existing search ranking. This is good, and it is what you want to happen. There are two distinct ways to do a redirect: temporary or permanent. The appropriate one to use is based on your situation. Is this a redirect for just a brief period of time or have you changed the URL for the foreseeable future? If it is permanent, your system should return a 301 status code which tells Google that it should update its index with this new URL. A temporary move should return a 302 status code, and Google will assume this is a short-term change and continue to hit the old URL when crawling (possibly being redirected every time). Google has suggested that either redirect will work equally well, but this is not true for other search crawlers and doesn’t seem to be completely accurate for Google as well, so make sure to use the appropriate type of redirect for your situation. Moz.com has a good write up on the various forms of redirection, including details on how to implement them on various platforms.

What if the URL is just completely gone? You didn’t move the page, you just deleted it. In that case, your site should send back a ’not found’ message and a 404 status code to users and search engine crawlers that hit the URL. This indicates the content is gone, which is true, and it will lead to Google removing it from its search results.

JavaScript #

This is a controversial topic, but I am going to share my point of view with you. For content on the web (not applications, like your gmail or outlook inbox), JavaScript should not be required to get to the content, it should be used only to add to the experience. This used to be essential for SEO, as search crawlers didn’t execute JavaScript, but that has changed and now Google manages to see content even when script is required. Google is not the only consumer of your site’s HTML though and you will get better results if the core of your content is rendered before any script is executed. To assess this state for your own site, turn off JavaScript (this is different in each browser, but this page has instructions for most), and then go click through your pages. Are you able to get to everything? Great, done. It is understandable that some functionality is missing, but my goal with any site is to ensure you can at least access the core content.

Structured Data and other ‘hidden’ elements #

In general, search engines read the same content that users see on their screens, so that should be the most important focus of your work. Your headings, your body paragraphs, those are the key. There are ways in which we can provide a bit more information to search engines that can enhance their understanding of your content. One example that we already covered is the “description” meta tag, to supply a short synopsis of the content, but there is a whole category of hints you can provide in the markup of your pages. This is a deep rabbit hole you could run down, and you may not see a massive return on that investment, so I will just touch on a few examples. You can find out more on Understand how structured data works | Google Search Central and Getting Started - schema.org.

Language #

This is part of doing valid HTML, but one that sites often missed. In the <HTML> element of your markup, you should specify what language your page is in (human language that is, not programming language).

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

This helps the search engine better understand your content and is a hint about who would find your content most useful.

Location #

If the physical location of your business matters because people need to find your store or restaurant for example, it is critical to make that information available on your pages. It should be one of the most visible pieces of information on your site along with your hours and other contact information. Search engines will pull this data out of your page as long as you haven’t done anything odd like put it as an image, but if you want to make sure it is understood by crawlers, you can provide it as machine readable information. You can do this by wrapping the content you already have or by adding a block of JSON data to the page (there are other official ways, but these are the two that I’ve tried and found to be accurately understood by search engines). To specify that you are in Seattle, WA for example, you could do either of these:

<div itemscope itemtype="https://schema.org/LocalBusiness">

<h1><span itemprop="name">Duncan's French Bakery</span></h1>

<span itemprop="description">A classic French bakery making croissants, eclairs, and macarons in Seattle, WA since 1986.</span>

<div itemprop="address" itemscope itemtype="https://schema.org/PostalAddress">

<span itemprop="streetAddress">123 1st Avenue</span>

<span itemprop="addressLocality">Seattle</span>,

<span itemprop="addressRegion">WA</span>

</div>

Phone: <span itemprop="telephone">206-123-4567</span>

</div>

Or, you can embed a block of JSON data like this

<script type="application/ld+json">

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "LocalBusiness",

"address": {

"@type": "PostalAddress",

"addressLocality": "Seattle",

"addressRegion": "WA",

"streetAddress": "123 1st Avenue"

},

"description": "A classic French bakery making croissants, eclairs, and macarons in Seattle, WA since 1986.",

"name": "Duncan's French Bakery",

"telephone": "206-123-4567"

}

</script>

Both would work and increase the chance that search engines will correctly pick up your physical address. Super important in the case of a business, less important for a site like Wikipedia or this blog :)

I have mixed feelings on which of these to use. The first option, microdata, is appealing because it ensures you are putting all this useful information in the real content and avoids having to duplicate it in another block of markup, but it may be difficult to maintain as you change the content using a CMS or as you change the design of the site over time. The JSON block (known as JSON-LD, or Linked Data in JSON) avoids having to do anything with the content of the page and can be an easier way for the site developer to have all this type of information in a single place in the code.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) #

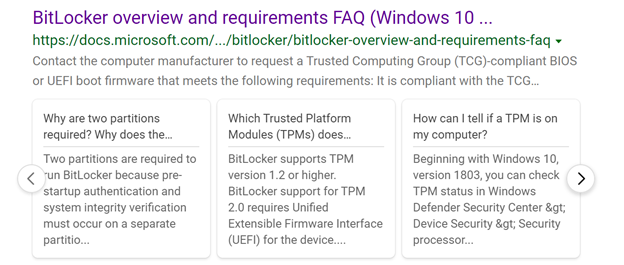

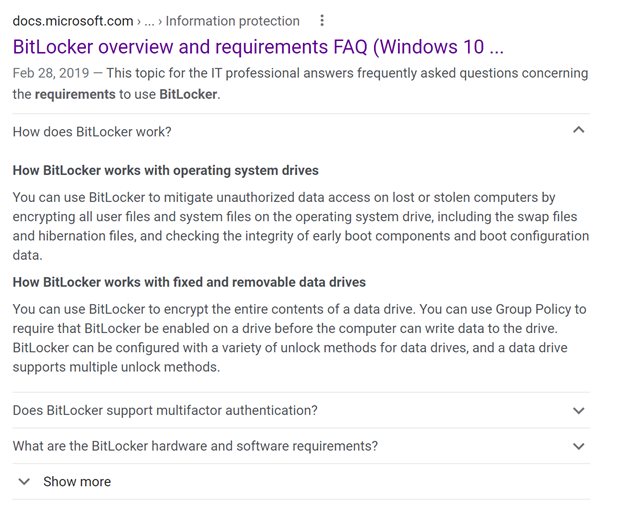

Frequently Asked Question pages are a common feature of many site, and if you can mark them up using structured data, search engines can take advantage of this information to surface the questions and answers right in the results page. For example, on the Microsoft Docs site, we have this page about Bitlocker, and in its markup there is a JSON-LD block

<script type="application/ld+json">

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "FAQPage",

"mainEntity": [

{

"@type": "Question",

"name": "How does BitLocker work?",

"acceptedAnswer": {

"@type": "Answer",

"text": "<p><strong>How BitLocker works with operating system drives</strong></p>

<p>You can use BitLocker to mitigate unauthorized data access on lost or stolen computers by encrypting all user files and system files on the operating system drive, including the swap files and hibernation files, and checking the integrity of early boot components and boot configuration data.</p>

<p><strong>How BitLocker works with fixed and removable data drives</strong></p>

<p>You can use BitLocker to encrypt the entire contents of a data drive. You can use Group Policy to require that BitLocker be enabled on a drive before the computer can write data to the drive. BitLocker can be configured with a variety of unlock methods for data drives, and a data drive supports multiple unlock methods.</p>

"

}

},

...

</script>

When this page comes up in a Bing search result, we get this neat experience, showing questions and their answers broken out.

And in Google, we see something similar.

A more appealing result can make your content stand out from the lengthy list of links, and in this case, it helps the user get right to an answer without even having to click through.

Intentionally excluding pages from search #

If you have a page publicly available, not behind a sign-in or other form of authentication, then it is likely that Google will end up crawling it even if you haven’t put it in your sitemap or shared it widely. This is good, it is what we normally want, but sometimes you will have a page that you would not want returned as a search result. In my case, I’m happy to have my ’tag’ pages crawled (like this one for posts about CDNs), it helps Google find all my posts, but I don’t want those kinds of pages to appear as a search result.

By adding a ‘robots’ meta tag you can tell the search engine crawler (the robot in this case) how you’d like it to treat that specific page. The two most relevant options are ’noindex’ and ’nofollow’. Noindex indicates that the search engine should not add this page into its index, which means it won’t come up as a search result. Exactly what I want for a ’list’ page that I want to exclude. Nofollow means that when the crawler finds links on this page, it won’t use those links to keep exploring and crawling your site. You can combine them or use them individually, making all these valid options:

<meta name="robots" content="noindex"><meta name="robots" content="nofollow"><meta name="robots" content="noindex,nofollow">

Index and Follow are also valid options, but those are the default and you shouldn’t need to include them in your page. In my experience, I’ve never seen a good reason for nofollow (but I’m sure there are some), as I want the crawler to discover everything, but noindex is extremely useful.

Just a reminder, this isn’t about security or protecting data, if you have information that is private your site should not even allow a crawler to see it. Put confidential data behind proper security, these ‘robots’ directives are just a little hint to search engines.

What about improving our position in the search results? #

Everything above here is about making sure search engines can index your content accurately. Now, if you have the capacity and inclination, you can start into content marketing or creating content to line up with your goals. For example, if you are running a bakery specializing in French pastries called “Duncan’s Pâtisserie”, you may want people to be able to find you by searching for “bakery near me” or “croissants in Seattle”. With that goal in mind, make sure your page includes the words “bakery”, “croissant”, and “Seattle, WA”. Don’t just stuff them into the page though, it’s best if it is part of the content. You could have a nice heading with a subtitle like

<h1>Duncan's Pâtisserie</h1>

<p>A classic French bakery making croissants, eclairs, and macarons in

Seattle, WA since 1986.</p>

And I’d recommend putting that information into the page description as well for the best results.

You should have realistic expectations for your position in search results. If you are a brand-new bakery in Seattle, you’ll be competing with existing businesses that have had tons of people link to them, have years of history on the web, etc. Showing up as the #1 result for “Seattle Bakery” isn’t something you can just make happen, but your first goal is to make sure you show up at all and appear in a local search or map view. Try out more specific search terms as well, if Seattle Bakery has you ten spots down, see where you show up for Seattle French Bakery, or Croissants near me!

Some last thoughts #

This is a large set of information, and yet it is only intended to be a shallow dip into the world of SEO and proper web site structure; it is understandable if you are a bit overwhelmed. You don’t have to do everything suggested in here, and you will find some issues that you don’t have time to fix, or that you just can’t figure out how to resolve. I have been doing this type of work for a long time, and yet I found issues on my own site as I went through this process. I’m going to take a few of the ones that bother me the most and fix them. Overall, despite those issues, my site is set up ‘correctly’ for SEO, even though it isn’t perfect. This is a sliding scale from ’not great’ to ‘better’, instead of a pure measure of right vs. wrong. Knowing something is an issue is a great first step and you can improve over time.

Thoughts on this post? Feel free to reach out on Bluesky!

Web DevelopmentCodingSelf-AssessmentSEO

6493 Words

Published

47bafe5 @ 2023-10-17