10 minutes

The inevitable result of focusing only on shipping features

Throughout my time leading engineers at Microsoft, there would often be discussions about the relative ‘velocity’ of our team over time. As our projects grew in size, it seemed it was harder and harder to add new features. I like analogies, so I have found myself going back to this description many times:

Imagine you have a construction company that designs and builds skyscrapers. They can create one new skyscraper a year. Assuming nothing else changes, they should be able to keep that pace up for the long-term. Now, after each new building project finishes, have that same team take over as the maintenance and operators of that building. It’s a small amount of work, relative to the full construction, but it takes a part of their capacity away, so the next building takes 13 months to finish. Now they take over the maintenance of that building as well. They are smart, so there are some efficiencies gained, but still, the next building takes 14 months to complete. Eventually, there are so few team members left to focus on the next project, that all progress stops.

If we are continually adding new features, the overall complexity of the software will steadily increase, and the surface area that we need to maintain will grow to an unsustainable state. I’m not suggesting that adding new features is bad, but we need to add them with the long-term product in mind. We need to see a continuous focus on restructuring/improving the product as part of our job, not a tax that takes us away from adding new features.

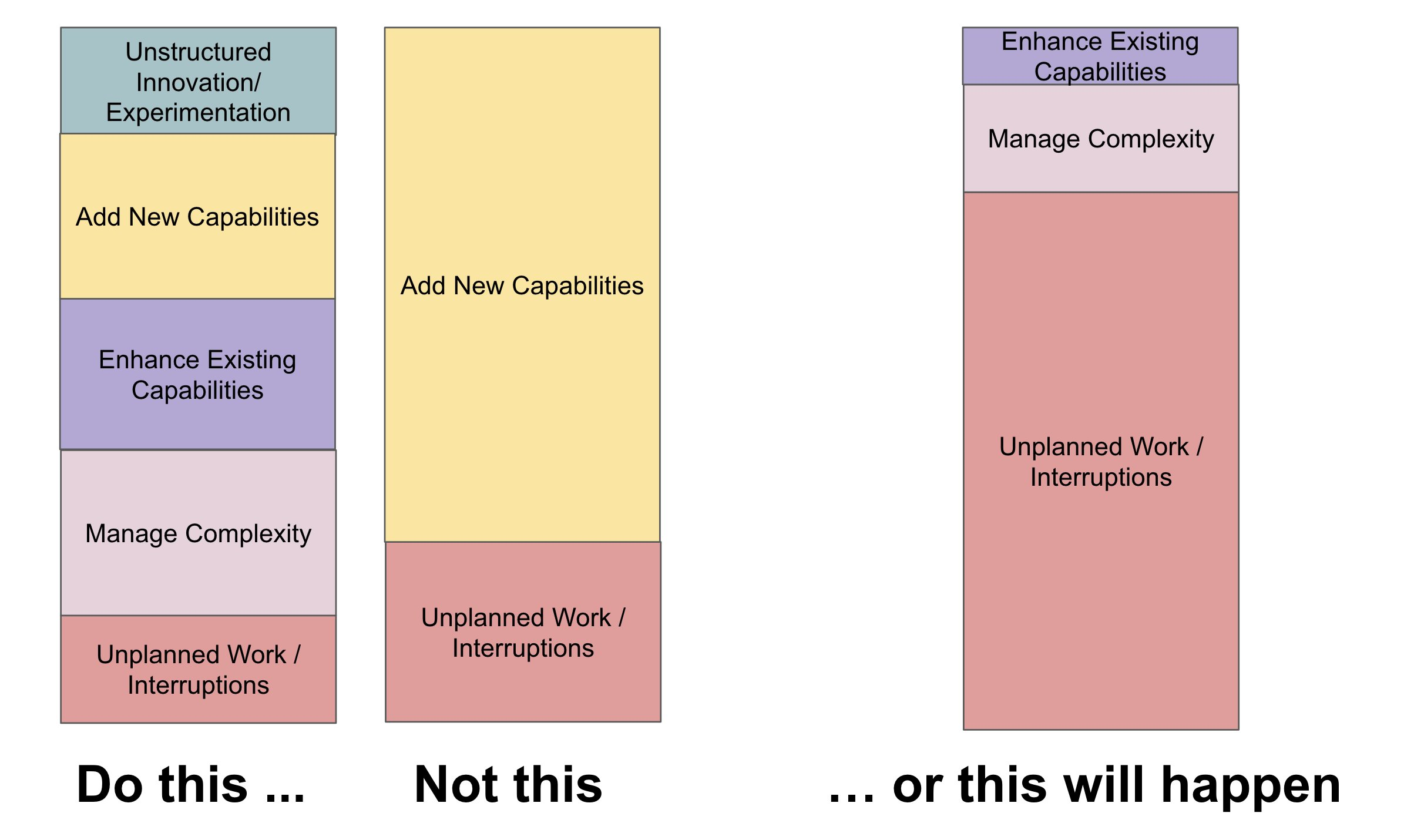

John Cutler posted this image to twitter recently that hits the same point.

How does this play out in the real world? I’m going to use Microsoft Docs as my example as I go through some thoughts on how a team can avoid getting into a complete gridlock where they aren’t able to make any forward progress.

Continuous improvement of the core of your product #

Unless you are early in development, your site/app/service is already delivering value to your customers. In the case of Docs, writers can create and update content as Microsoft ships and updates products. Ensuring that publishing flow is reliable, and that the content is available for our customers to consume is our core purpose.

There is a huge team and workflow around that content, and I would treat it as its own distinct product, that faces the same challenges we are talking about here. If they only add new pages, without restructuring and improving what is there, eventually the quality of the complete set of content will drop so low as to be useless. I’m not going to talk much about that side of things here, but that team is continually managing their project to avoid that exact problem.

Fixing bugs that impact that core functionality is critical, but so is ongoing improvement. Can we make the site more reliable? Can we make the publishing workflow faster and easier? In many ways, these improvements are more important than new features, because we are improving capabilities that we already have people using. As we improve our knowledge of accessibility, we need to update our experience to be easier to use, a continual set of work to keep our baseline experience available to all our customers. Maintaining the core capabilities of the system is our top priority and enhancing that core is a close second. If this truly is delivering value, we don’t want that functionality to degrade.

On your team, everyone needs to agree and understand this basic concept. Keeping the core value proposition of your system up and running is the job, it isn’t overhead or a tax that keeps you from doing some other work. If you feel that you are not able to accomplish this with your current team, then you do not have the capacity to be adding to the scope of this product.

Quick side note here, if all your capacity is taken up running the current system, bringing in a set of vendors to build a new feature will only add to this problem. Yes, they may be able to build a new feature, but they’ll need some of the team’s time if they are going to understand the current system and integrate the new feature in a logical way. And, once they finish, you have an increased surface area and more functionality that needs to be maintained. You are in a worse place than before.

Sustainably adding new Features #

What if you do have the capacity to work on adding to the system? I’d suggest there should be careful consideration to make sure a new feature is more impactful than enhancement of what you already have, but if you do decide to expand the capabilities of your system you need to do so in a sustainable way. When the business has a need, the goal is to add it to the system in a way that fits into the existing functionality, aligns with the product roadmap, and adds the minimum amount of new surface area.

On Docs, the content team creates pages using components and templates that the development and design team have built. When we need to create a new experience, such as a redesigned Learn home page, we could go around our template system and make it in HTML. In the very short-term, this might save us a lot of time, but we would have:

- Broken our model of self-serve content updates,

- Added a new one-off experience to test and update for security and accessibility, and

- A page that we will forget when we have wide-sweeping updates in the future.

The right approach is to determine how this new page fits into our existing system, create some new components in our design system (or alter existing ones for the entire site), reuse an existing template with these new options or make a new one if that’s the best decision. In the end, we have some new components that we will know to maintain on an ongoing basis, and if we ever want to make a site-wide set of updates to our styles or markup, we have our catalog of components that covers everything we need to support.

Some people will shout “premature optimization” and “YAGNI”, because we are doing an expensive set of work for something that might only be needed once. In the case of a new page on Docs, I’d ask how long it will be live, and if the answer is more than a few months, then I already know we need to build a sustainable solution. The updating and maintenance of this page is going to be a drag on the team if we don’t build it correctly from the start. For other feature requests, it is not always so clear.

We were asked once to add a banner to the site, advertising an upcoming event. This was unusual and there was no way to know if it was going to be an ongoing need, so the team solved the problem with an unsustainable, one-off bit of code. Still good code, still reliable, but not easily updated and required engineering work for each new banner. After a time, it became obvious that there was going to be a steady stream of these banners, so this is when the need to ‘manage complexity’ comes in. We could have just continued to do these banners one at a time, but the right approach was to take a step back, document the desired state (where updating banners was self-service) and then build that.

A one-off solution, without a near-term date to replace or remove it, is never the right idea. Even if it is unique and you’ll never need to do it again, eventually you’ll have a thousand little bits of ‘special’ code that we never really integrated into the system. This is the quickest and most common path to an unsustainable code base.

Sustainable engineering is about meeting the business need with the most maintainable solution that adds the least complexity and surface area to your project.

Growing the team to handle increased scope #

Even the most carefully planned project will grow in complexity over time if we continue to add functionality. Building features in a sustainable fashion will reduce the impact of each new capability, but eventually you still get to a point where the capacity available to build new features is too low to be productive. To get around this, we add more people to the team, which can create its own problems. No matter how many people are working on it, a complex system is harder to maintain and build upon, so we need to look for opportunities to treat specific elements as their own subcomponents.

There are many ways to split teams across large projects and I’ve seen each method succeed and fail, making it hard to dictate a single way to look at this. What I will say though, is to look at this problem from both the product side and the implementation side.

Look at your product and identify areas with distinct functionality or audience. Have squads of people focus on those areas, building the unique capabilities of each. From the implementation side, all areas have certain shared dependencies (like a design system or user authentication) that would also benefit from dedicated teams.

Channel 9, for example, has a video-encoding system, that is essential to getting content published, but it is also very decoupled and only interacts with the site through some internal APIs. If we had the resources, having a distinct squad on that system would have been an effective way to grow our capacity.

The lines between these areas should be fluid though, if a new feature requires a change to the design system, that should be something either the feature team or the foundational team could do, with the other team helping to review. With rigid separation of responsibilities, you will quickly end up with bottlenecks and delays. In our Channel 9 example, if we needed an update to the size of thumbnails as part of a front-end feature, it may be easiest to let the ‘video encoding’ team do it as they know the code the best, but we should be open to just having the team that needs the update do a pull request that has to be approved by the video encoding team.

There are many ways to create smaller teams that can be effective, but there is one method you should never do. Do not create a maintenance team, or a bug fixing team, or alternatively a ‘incubation team’ that builds the cool new features. If you want unsustainable growth, with the highest increase in complexity over time, this is the path to that result.

Everyone needs to be thinking of the ongoing health and maintenance of the system. This is one of the reasons why bringing in an external vendor to build a new feature, allowing pull requests from other parts of the company, and even a hackathon (as fun as that sounds) can all push a system farther towards an unmaintainable state. In each of these cases, the people doing the new work do not understand how this new complexity will impact the system and they aren’t going to keep maintaining it in the future. To make these scenarios work, you need the main team working on any new feature and owning its full lifecycle.

Growth without the crushing weight of complexity #

A common pattern in large software systems is that they grow in scope over time, leading to a state where they can no longer move quickly or keep up with the regular ongoing work needed. Eventually they die out or someone must rebuild them from the ground up. The business or the engineering team makes this decision because it seems like the easiest path forward. This doesn’t have to be the case, but to avoid it requires a mindset change. A focus on reducing complexity and sustainable growth. A preference for enhancing our core functionality instead of adding new capabilities. There are definite reasons for new features, they can be critical to the product, but we must build them with an awareness of their cost. We also need to be aware of what we are celebrating and creating incentives around. Is work done to improve maintainability, efficiency and existing functionality given equal weight to shipping something new and shiny? I suspect that if it were, we would have more stable and reliable software that could avoid the eventual demise of so many projects.

Thoughts on this post? Feel free to reach out on Bluesky!

Web DevelopmentCodingSoftware ManagementEngineering Management

2109 Words

Published

878f2f6 @ 2023-09-28