10 minutes

What is a CDN, how does it work, and should you use one?

I’ve been working on websites at my day job and on my own for many years now, and in that time I have ended up explaining CDNs (Content Delivery Networks) to a lot of people. I think most people have some idea of what they are (and many probably know them really well), but for anyone who doesn’t, or who might want a tiny refresher, I thought I would go through what they are, how they work and how to decide if they would work for your situation.

What is the problem we are trying to solve? #

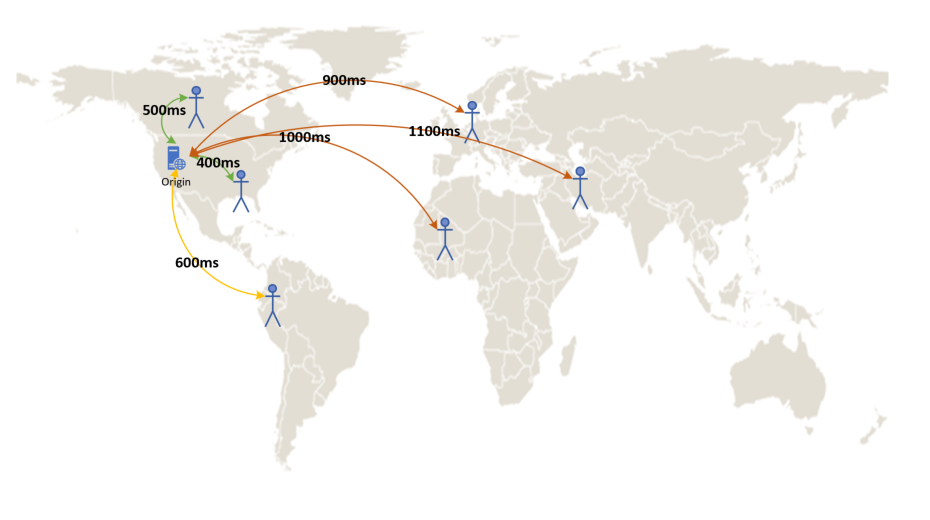

The interaction of your browser with a website is primarily a whole bunch of requests to send data from the web server to the user’s machine. If you think about the initial request for a page (for example https://www.duncanmackenzie.net), that’s a request, and then once that page comes down, the browser will have to request some CSS files, some images, maybe some fonts and probably some JavaScript. In the end, the browser will have made requests for, and then received, a ton of different pieces of content (stats on the # of requests required per webpage for 2019). Each of those requests has to travel from the user to your server, and the response has to travel back. That is a lot of travel time, and the farther away the user is (it isn’t really about actual physical distance, but it’s roughly accurate and easier to think about), the slower it takes for that request and response to happen. This transmission time, known as latency, isn’t something you can speed up by writing faster code or buying a bigger server; it just takes time for data to get from place to place.

Looking at my site for an example, there is a server in the Azure region ‘West US 2’ that is hosting my pages and is physically located somewhere in Washington state in the USA. If I request the page from various locations around the world (I used a free utility from https://www.dotcom-tools.com/ to generate these #s), you can see the response times (lower is faster and better) in this table:

| Location | Response Time (in milliseconds) |

|---|---|

| Seattle | 543ms |

| Dallas | 449ms |

| Madrid | 982ms |

| Paris | 1000ms |

| Frankfurt | 983ms |

It isn’t completely linear, the response time in Seattle is actually lower than the response time from Dallas, but if you look at locations in Europe, they are all much slower than locations in North America.

Visitors from some parts of the world are going to get a slower response to my website compared to one located in their own country. This might not matter that much if I was a small-town newspaper (although the world is more and more global; what if that newspaper has a story that goes viral?), but if my goal is to serve a global audience, then this is a bad experience.

Making your page smaller, making fewer requests, and making your server faster can all help to improve this experience, but after doing all of that, you will still be limited by transmission speed. The only way to speed things up would be to move your server closer to the user.

If you have users all around the world though, picking a single location is a challenge. Given enough money, and a good cloud provider, you could deploy your site to servers in many different countries and that would definitely help, but now you have new problems. How to deploy to n different locations? How much will it cost to run your site in all these places (possibly including a database or other type of resource would also need to be deployed to all of these regions as well)?

Which brings us to CDNs.

What is a Content Delivery Network (CDN)? #

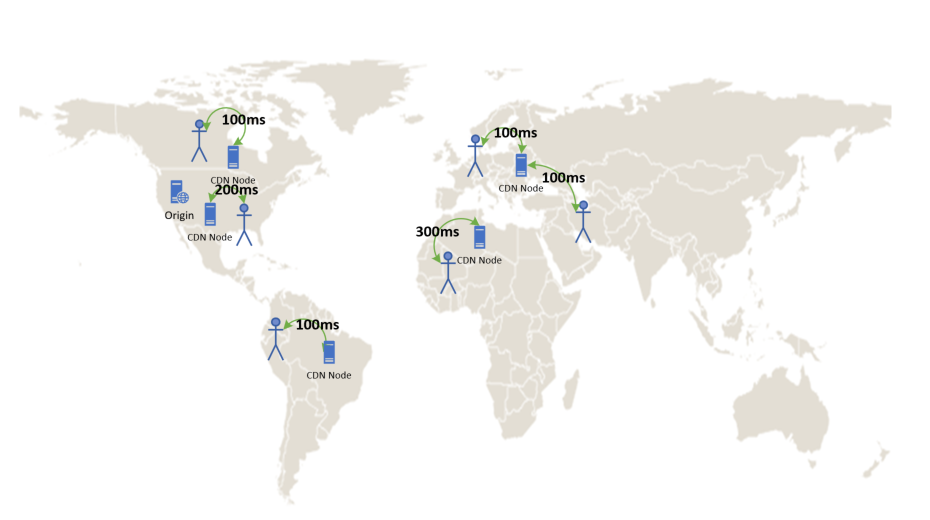

A CDN is just another form of cache, a way to hang onto data in a convenient place to avoid a more expensive action. In this case, the expensive action is going back to your server (potentially running code, hitting a database, or maybe just reading from disk), and the convenient place is lots of places that are much closer to the user.

A CDN is a system of machines setup to respond to requests for a given piece of content. These machines are placed all around the world to ensure they always have one relatively close to the user making the request.

You configure an account with the CDN provider (the company who owns all those machines around the world, like Akamai, Verizon, CloudFlare or others) and setup a mapping so that they know where to get your content when people ask for it. That source is called the ‘origin’ and all of those CDN servers are called the ’edge’. Going through this for my site, for example, I create an endpoint with the Azure CDN called ‘duncanmackenzieblog’ and tell it that my origin is ‘duncanmackenzieblog.z5.web.core.windows.net’. I then map the custom domain ‘duncanmackenzie.net’ to this CDN profile, and now any request for my site is going through the CDN. The CDN provider sets up their DNS so when a user tries to connect to duncanmackenzie.net, they’ll be given the IP address of the closest CDN server.

What does it do? #

Now, if the user requests ‘duncanmackenzie.net/index.html’, they’ll be connected to that close CDN edge server (quick connection time, because it’s close), which will in turn fetch ‘/index.html’ from the origin and return it back. If we stopped right there, we might see some benefits, because the user is connecting to and communicating with a closer server instead of going all the way back to the origin server, but the edge is still making that request, so that long distance call is still happening. The CDN is smart though, and it can hang onto the response from our origin and serve it as a response to future requests. This removes the need to go back to the origin for that content after the first request, but also takes that load off our origin server.

So, three benefits rolled together:

- the user is connecting to a server closer to them,

- that server may have the content cached and can return it immediately, and

- in that case, it doesn’t even hit our origin server (less load, less cost)

With all of that setup, I can run the same test as earlier, requesting a resource from 5 cities around the world. This time we hit the CDN mapped domain (duncanmackenzie.net) and got these results:

| Location | Response Time (in milliseconds) | no-CDN time | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seattle | 475ms | 543ms | -68ms |

| Dallas | 612ms | 449ms | 163ms |

| Madrid | 479ms | 982ms | 503ms |

| Paris | 325ms | 1000ms | 675ms |

| Frankfurt | 299ms | 983ms | 684ms |

Seattle and Dallas don’t show a huge difference (Seattle’s even a little slower, but some variation is normal and if I ran this test 10 or 100x it would average out), but look at the European locations. More than a half second difference (and this is per request so the latency will have a 2-3x impact on your overall page timings). Even for the closer locations, the CDN is offloading the request from our origin server, reducing our server load and cost. With caching setup, now the user may be able to request a page from your site and all the traffic will happen between them and the (close) edge server provided by the CDN.

Cache Hits and Misses #

Sometimes, when the user requests a given resource (a page, an image, a CSS file, etc), the CDN will check it’s local cache and realize that it doesn’t have a copy of that resource, or that the copy it has is too old (based on the cache settings, described below).

CDNs can be configured to cache content either using rules in their configuration (keep copies of all content for up to 24 hours), or by being configured to just respect whatever cache header comes back from the origin server (keep copies of the content for as long as the origin said was ok).

At this point, the CDN will fetch a new copy of the resource from your origin, send it back to the user and update its local cache. This is called a ‘cache miss’, and when it happens, that one request might take a bit longer than normal. Any request where the CDN does have a copy and can return it directly is called a ‘cache hit’. At no point does the user ever connect directly to your origin, the CDN servers handle those requests when needed, the user only deals with the CDN. The goal when using a CDN is to try to end up with a higher # of hits than misses, so that the CDN is doing most of the work instead of your server. The amount of your traffic served by the CDN is the ‘offload %’, and a number above 90% is generally considered excellent.

When should you use a CDN? #

I’ll cut to the chase here, and say you should always have a CDN in front of your web content. Having said that, it definitely works better in some situations than others, depending on what caching rules you need to use for your content. If, for a given URL on your site, you send the same response to everyone who asks for it, that content can be cached. Now the CDN edge will ask your server for that data once, and happily return it to your users for however long you have specified that it is still a valid response. If you have a page where the content is different for each user (like a list of recent orders on an e-commerce site), then you can’t let the CDN cache that, as that would lead to showing one user’s data to a whole bunch of others. Instead, in this case, you’d set your cache headers to indicate this is a private response (cache-control: private or cache-control: no-store). Usually your web site will have either all cacheable content, or a mix of both cacheable and private responses. In this case, setting up a CDN and mapping your domain to it is still the right thing to do. Now you can setup different caching rules for different pages without having to use a second domain like static.duncanmackenzie.net to return your cacheable resources, which avoids a second domain needing to be looked up and connected to. Even in the case of private content, the initial connection and SSL negotiation all happens between the user and the edge server, and that will be faster than going back to your source. With any type of content, you will see a benefit, but if your content can be cached there will be a bigger impact.

Summing it up #

That is it, the basics of how a CDN works. Looking around you will find that there are tons of different CDN companies, and all of them do the basic functionality described above. Beyond that, they usually offer a bunch of extra functionalities that are awesome and might be perfect for you, but if all you care about is the basics then the various companies will differ based on:

- How many edge servers do they have, and where? The CDN company’s marketing site will often talk about their ‘points of presence’ and show maps with tons of dots showing how broadly they are available around the world.

- How fast their servers are, and how fast their internal network is. The first will impact how quickly they can respond to requests from the user, and the second will impact how long it will take them to fetch content from your site when needed.

- How much they charge to serve your content. This can be priced based on the # of requests they have to handle (and keep in mind that a single web page could take 10s to 100s of requests to be fully loaded) or by the amount of data they are transmitting around for you. Some will even have free tiers if you are dealing with a small amount of traffic.

Thoughts on this post? Feel free to reach out on Bluesky!